With a wildly successfully sequel and extensive modding support for the original release, The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion Remastered falls in an unfortunate middle ground.

I’m part of an audience of existing fans happy to purchase another Elder Scrolls game several times over, no doubt thanks to a heady dose of nostalgia for time when we had the time to “live another life, in another world”. However, there’s a reason they went with “remastered” in the title instead of “remake”, and I feel your history with the game – if any – could have a significant impact on your experience.

Honestly, I’d have preferred The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind received this level of attention, but there’s no denying Oblivion was instrumental in popularising the IP on consoles and it laid the foundations for the success of The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. Still, after 25 hours spent following the primary questline with a few diversions, it’s easy enough to recommend this remaster if you’re after a mostly vanilla Oblivion experience in 2025 (assuming you have the hardware to run it).

For newcomers or those who loved Skyrim but missed Oblivion for whatever reason, it’ll scratch a lot of familiar itches – so long as you can accept its fledgling mechanics and systems can feel underdeveloped and even more janky at times. For returning fans, it’ll depend on your tolerance for Oblivion’s most notable failing.

For newcomers, The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion Remastered is, unsurprisingly, set during the “Oblivion Crisis” – an event often mentioned in Skyrim as the catalyst for the rise of the Third Aldmeri Dominion that would go on to fracture the Empire unified under the Septims.

Your protagonist is another prisoner who finds themselves swept up in events and during a bland cave- and sewer-based tutorial, they witness the assassination of the emperor; they’re tasked with finding a hidden heir to the throne; and told to help him “close shut the jaws of Oblivion”.

Of course, this is an Elder Scrolls game so you can pursue those instructions with vigour or just ignore them for hundreds of hours if you wish. Almost two decades on, Oblivion still excels at what Bethesda Game Studios have always done well: presenting the player with a massive world to explore, packed with things to see and do, and the flexibility to tackle it in any way you choose – in theory.

You craft your would-be hero using a horrific selection of cosmetic options somehow worse than the original; you wade through innumerable tutorial screens; pick your starting class, major skills, and star sign; and finally emerge into the high fantasy-inspired heartland of the Empire, Cyrodill.

The primary quest points to a small priory to the north-west; the Imperial City looms over you; there’s a dank cave entrance or beautiful Ayleid ruin near at hand; and the map screen provides a half-dozen other cities you can instantly fast-travel to. It’s still a sensation as overwhelming as it is exhilarating even in 2025.

If you prioritise the primary quest, you’ll be knee-deep in cultists, Oblivion portals, and Daedra as you seek the last Septim heir and fight back against the schemes of Daedric Prince, Mehrunes Dagon. Alternatively, you can join and climb the ranks of the fighters, mage, or thieves guild – each dealing with nefarious plots to destabilise them from within and without.

You can seek out Daedric shrines to complete a mix of questionable and often hilarious quests to gain their favour and unique gear, or you can just travel from city to city, solving local problems that are sometimes exactly what they seem but often come with unexpected twists.

On paper, and for a dozen or so hours, Oblivion really sells that “live another life, in another world” premise. It’s also at its best when tackled organically. I’d neither recommend mainlining the primary quest, nor systematically clearing every location on the map. The end-of-the-world threat will happily wait on you and, attempting to do everything, everywhere, all at once, just highlights the AI routine limitations and dialogue inconsistencies.

If you just go with the flow – mixing up exploration and combat with persuasion challenges, thievery, and alchemy – it’s easy to get pleasantly side-tracked for hours at a time and better immerse yourself in a game world that, when studied too closely, is bizarrely dense yet underpopulated.

Of course, all open-world games face the same challenge: how do you keep players engaged while maintaining some semblance of pacing when you’re offering up a hundred hours’ worth of questing and dungeon-delving?

Oblivion’s answer was level-scaling. The idea being no matter what path you took, you’d face off against increasingly tough enemies with your upgraded skills, while looting higher-tier gear from their corpses or chests (with increasingly tough locks).

It was a noble but inherently flawed effort, and it remains an issue the remaster has lightly tweaked but not resolved. The obvious problem with this design is that level-scaling robs the player of any sense of meaningful progression for much of their playtime.

The need to balance player progression and the difficulty curve is always an issue in RPGs, but the modern approach is to reward over-levelled players with an easier time on the critical path, while still providing optional challenging content and the promise of greater rewards to keep them engaged.

In Oblivion, you’re constantly improving your skills through use, boosting attributes each time you level-up, and you’ll be looting or purchasing better gear and spells as you go; however, every combat encounter and dungeon-delve plays out much the same way for several dozen hours.

It’s a sensation compounded by the fact Oblivion is still more RPG than action game. You can stay mobile and block or dodge but combat ultimately boils down to hitting things with blades, arrows, or spells until they die. Progression is measured by how few hits it takes to kill something.

It’s only when you unlock the highest skill perks and access game-breaking enchantments – such as Chameleon-enchanted armour and paralysis-enchanted weapons – that it’ll satisfy the typical RPG power fantasy.

It should also come as no surprise that level-scaling can play hell with quest design and what passes for rudimentary set-pieces.

Skyrim had its moments, but I feel most fans would agree the sense of exploration and the prospect of discovering something unique-ish was the main draw, not the quest design. Oblivion nails the first part, but you’ve got even simpler quest scripting, clunky set-pieces, and no traditional companions to liven things up

Quests are typically a variant of “go here”, “fetch this”, or “kill that”, with the most memorable boing those that offer multiple or unexpected outcomes. However, those are almost always standalone quests that will, at most, result in a different reward item or trigger a new generic line from townsfolk when you bring up the topic.

Oblivion is notable for introducing the “Radiant AI” system to give NPCs a simple daily routine that is significant to some quests, but it doesn’t take long to realise the bulk of scripting boils down to whether an NPC is in possession of an item, at a location, or flagged as dead.

Many of these basic quests are elevated by hilarious writing, goofy voice work, and plenty of animation jank, but the bulk of your time is spent away from settlements, scouring overlong, multi-zoned dungeons or Oblivion planes on your own.

Expendable NPC companions that feature if a handful of quests don’t benefit from level-scaling and die almost instantly if you’ve out-levelled them – either in battle or through sheer stupidity – leaving you alone once again to slog through hordes of enemies.

The only way to circumvent this is to exploit invulnerable plot-critical NPCs, dragging them along as silent but useful damage sponges without completing their respective quests.

Although The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion Remastered does little to address the game’s fundamental flaw, it does include some significant gameplay tweaks to go along with the gorgeous Unreal Engine 5-powered visual overlay.

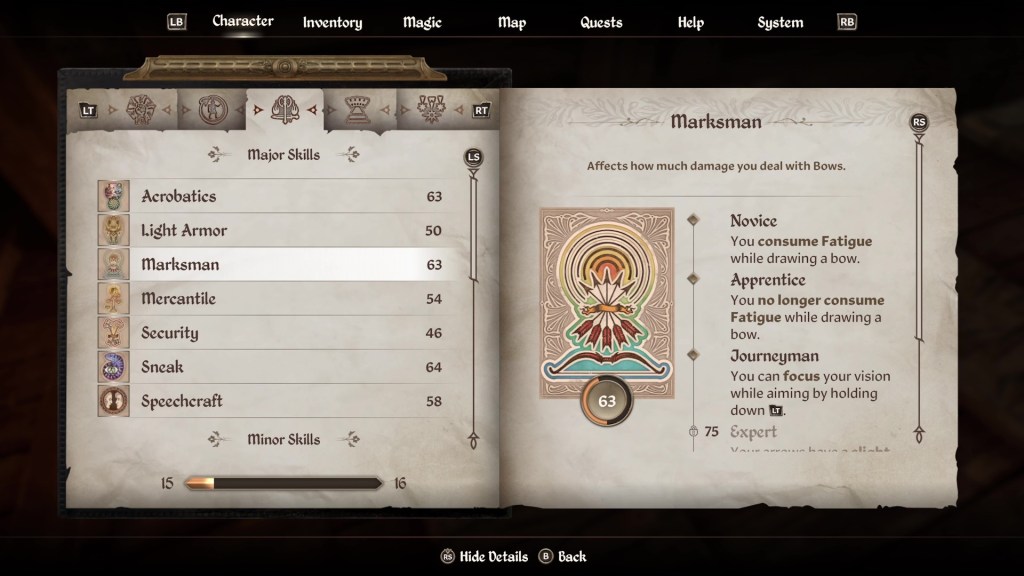

The most impactful changes are how both major and minor skill gains now contribute towards the player level, and which skills you improve no longer influence how many points you can boost attributes. You simply earn 12 “virtue points” each level, which you can invest across three attributes of your choice. You can still make your own bad levelling decisions, but as you retroactively gain health for strength and endurance boosts, it removes the likelihood of non-combat classes being one-shot at higher levels.

There is also a range of smaller but welcome changes, like more responsive menu-ing, increased movement speed and sprinting, health regeneration outside of combat, more reliable stagger animations based on where you aim, no fatigue penalty to attack damage, reliably recoverable arrows that both fly faster and hit harder, and tweaks to skill perk tiers – some new, some adjusted, and some just rearranged so you gain access to more useful ones earlier.

Despite these changes, old problems return when trying to boost combat-related skills if you realise you need a melee/ranged fallback, or maybe some elemental damage spells for resistant enemy types. The only sensible approach is to find and pay trainers, as low-level weapon skills and damage-dealing spells become laughably ineffective against higher level foes.

I’ve got this far without praising the audiovisual enhancements and, for returning players, it’s an impressive overhaul that turns Oblivion’s distinctive but barren landscapes and interiors into something akin to a modern release.

Geometric complexity, textures, vegetation, water, weather, environmental details, character models, movement and attack animations, lip-syncing and facial expressions – they all take a generational leap in quality, albeit not always a consistent leap.

I’d argue the global illumination system for the sun, moon, and other light sources feels most transformative, bathing the world in more realistic and atmospheric shades of light and dark. Oblivion always did creepy interiors well, and they feel even more terrifying this time round.

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion Remastered touches up the voice work without changing the weird, wild, and openly prejudiced (in-universe) dialogue, something most notable during hilarious NPC interactions driven by the Radiant AI system. These exchanges rarely have logical replies or a consistent tone, yet the system excels at antagonistic conversations between NPCs of difference races and class (in the socioeconomic sense). There’s also limited new voice acting to better differentiate Tamriel’s many races, while some NPCs that previously had multiple voice actor lines assigned to them have been fixed.

Combat audio effects and ambience have been added to improve combat and exploration respectively, though volume levels can feel off compared to the original. In contrast, the soundtrack needed no tweaking as it still holds up brilliantly, providing memorable orchestral themes for any scenario.

All that said, the gameplay tweaks and audiovisual updates can only do so much when the aged Gamebryo engine is presumably chugging away just below the surface.

The increasingly repetitive nature of Cyrodiil’s overworld and dungeons is hardest to disguise, particularly when maybe two dozen quest-related locations feel truly unique in appearance or design (and The Shivering Isles expansion accounts for much of this).

Every asset used to build the world has clearly been overhauled in The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion Remastered, but it’s not clear if any new assets were created. The bulk of Cyrodiil is still rolling, forested hills, while the “dungeons” are crafted using just a handful of tile-sets – think cave, mine, ruin, fort, city, and Oblivion plane – each with a limited number of building blocks. The world also retains its segmented nature, with dungeons, cities, the structures within them, and even each floor of some structures connected by loading screens.

You could argue Oblivion’s dungeons are typically larger and more elaborate than Skyrim’s convenient loops, but very few have memorable puzzle rooms, unique vistas, or anything close to the epic scope of the Blackreach Cavern. It becomes a serious problem when there are well over 200 dungeons to explore and, depending on your approach to the tackling the main quest, up to 50 Oblivion portals that can spawn.

Is all this content mandatory? No, but even sticking to the primary questline left me frustrated with the degree of repetition in this replay.

Returning to my opening line, it leaves The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion Remastered in a weird place. Given the response, it feels like a project targeting fans of the original – yet it retains many flaws that’ll quickly frustrate those fans. The visual overhaul and gameplay tweaks are an improvement – and there’s no denying the power of nostalgia – but it’s unlikely these remastering efforts would push me to complete it again over a modded version of the original.

With that said, I feel it’s newcomers to the IP or curious Skyrim fans that might benefit the most from this release, as they’ll find it easier to look past Oblivion’s flaws as they experience the wonder of simply exploring Cyrodiil’s cities, countryside, and dungeons for the first time.

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion Remastered was played on Xbox Series S|X using an Xbox Game Pass subscription. It is also available on PC and PS5.