As a fan of the immersive sim genre, it’s hard to decide which was the greater tragedy: having to wait 18 years between System Shock 2 and its closest spiritual successor, Prey (2017); or watching Prey (2017)’s developer, Arkane Texas, forced to churn out Redfall in 2023 before being unceremoniously shuttered by Xbox. At least that year Nightdive Studios’ remake of the first System Shock finally arrived on PC, after a turbulent 8-year development cycle that included IP licensing concerns, extended periods of silence, three complete restarts, and a shift from Unity to Unreal Engine 4. To their credit, the result was mostly worth the wait.

Replaying it by way of 2024’s excellent console ports (for both current- and last-gen hardware), the System Shock remake is faithful to a fault in some regards, but still infinitely more playable without the original’s clunky FPS/point-and-click hybrid controls. System Shock (2023) is far more involved than a traditional FPS, but it controls like one and works well enough when using a controller – aside from sluggish inventory management and an awkward lean toggle.

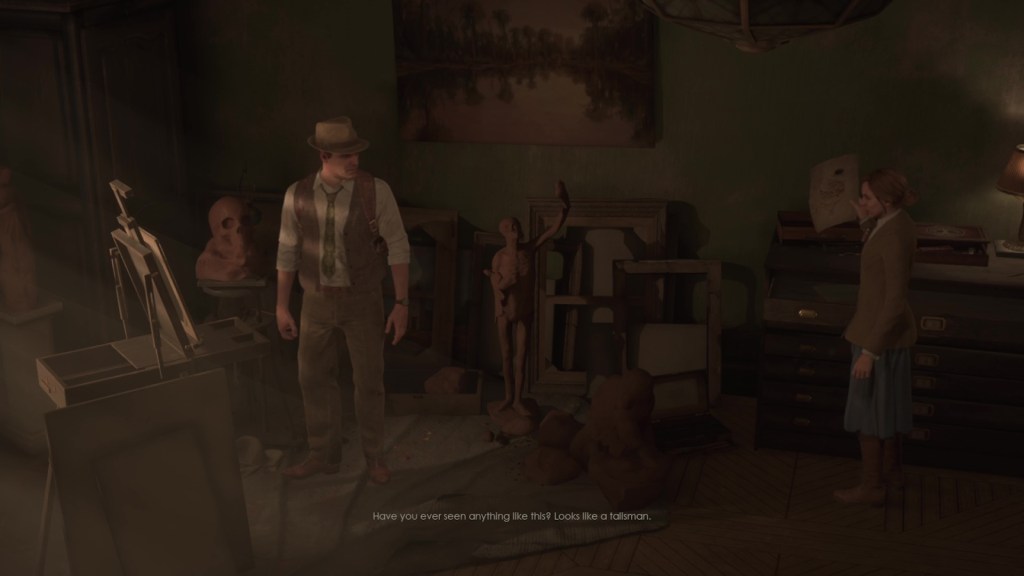

The updated UE4 visuals and new synth-heavy renditions of the original soundtrack generate late-‘80s/early-‘90s sci-fi vibes – think harsh lines, retro-futuristic tech, an abundance of specular reflections, and overblown neon lighting – and those fresh visuals are enhanced by a pixel filter that adds a veneer of retro-inspired chunkiness to close-range textures, character models, and 3D objects.

While the audiovisual overhaul and updated control scheme are obvious changes up front, System Shock (2023) deserves more praise for how it manages to recreate much of the original’s level design, mission flow, and iconic encounters, despite expanding and enhancing every element.

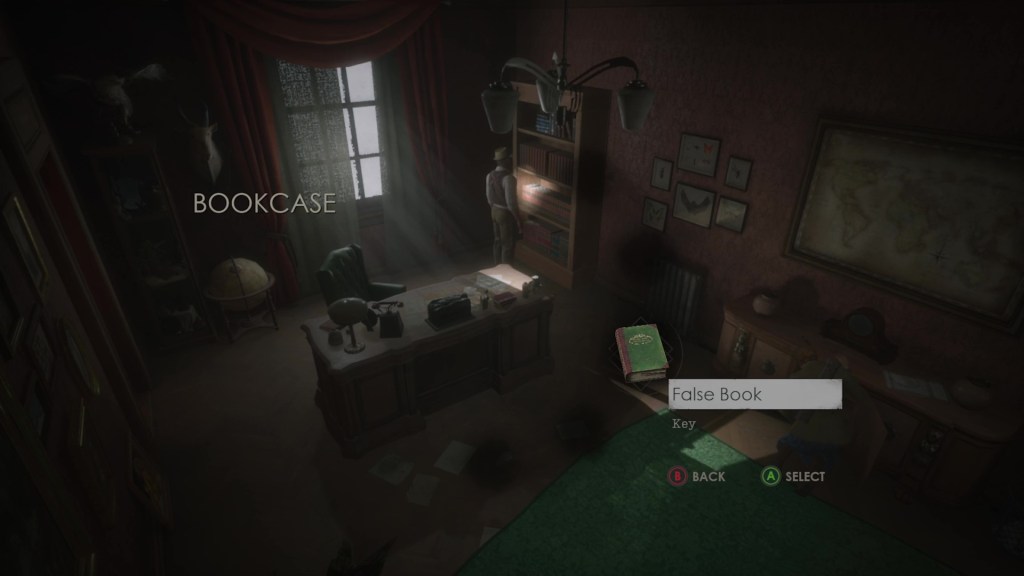

Moving through the multi-level and often maze-like Citadel Station still feels tense and sometimes terrifying, especially given how little handholding there is and the high level of challenge. In stark contrast to the “follow-the-icon” mentality of most modern games, you need to pay attention to your map and signposting to navigate. You also need to parse radio transmissions and audio-logs for clues on how to progress, slowly piecing together the desperate plans of the former crew.

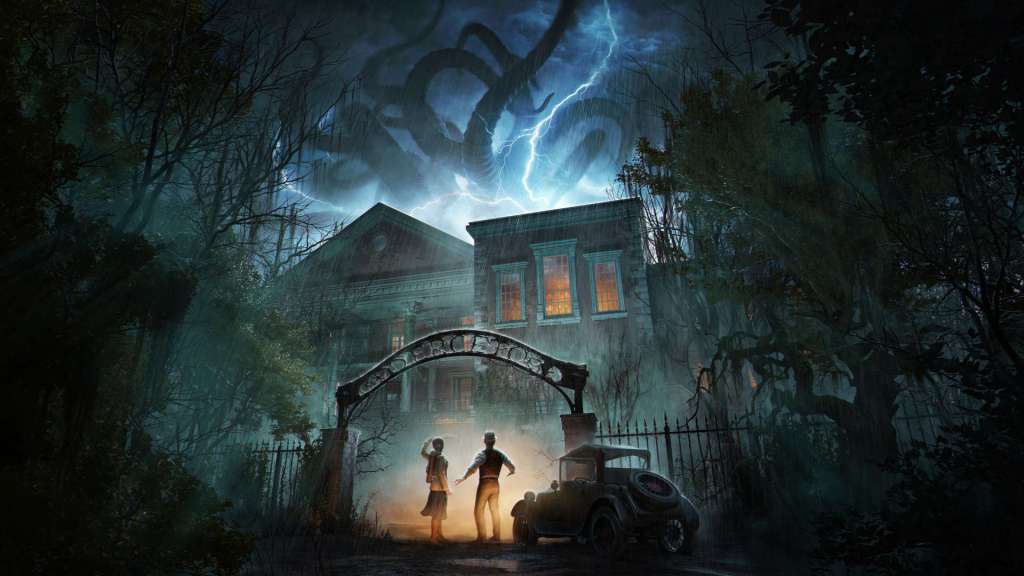

It helps that System Shock has a cliched but compelling “AI gone rogue” plot. After being arrested for attempting to steal designs for a Tri-Optimum neuro-mod, your hacker protagonist finds themselves transported to Citadel Station and confronted by Vice President Edward Diego with a simple offer: become part of their dubious experiments or utilise their skills to remove the ethical constraints on the station AI, SHODAN, and receive the modification they were after as a reward. Emerging from a medical pod six months later, it turns out unshackling an AI with a god complex was a poor choice and she now wants you crushed like an insect.

It’s a great setup, but aside from a handful of calls from survivors or Earthside Tri-Optimum staff, the bulk of storytelling is conveyed through optional audio-logs that near-perfectly correlate with environmental details. The more attention you give to the narrative elements, the more you get out of them.

A first playthrough also nails the sensation of awakening amid a disaster, alone and out of your depth. However, the updated mechanics and returning difficulty levels allow you to tailor the experience to be more forgiving of rushed exploration, poor planning, or scrappy combat.

The overhauled UI and menus better track progression, grid-based inventory management and quick slots for combat are a godsend, and you can customise the difficulty of individual systems. You get simple map markers on the easiest mission difficulty or a 10-hour time limit on hard. Combat is always challenging, but you can tweak incoming damage, mob sizes, and the respawn rate. Cyberspace battles – which play out like classic 6DOF shooters – can be colourful diversions or bullet-hell chaos. Puzzles – a mix of balancing voltages, rerouting power, and finding codes – can be brief distractions or leave you wishing you had a logic probe to simply override them.

There are fans of the original that would suggest maxing every difficulty aside from enforcing the time-limit for a first playthrough, but I’d argue even on the easiest settings, System Shock (2023) never loses that inherently challenging immersive sim core. Running straight into a horde of cyborgs is likely to see you shredded regardless of the difficulty, while too many scrappy fights early on will leave you short on supplies and forced to adapt.

The ability to revive at Restoration Bays is available regardless of the difficulty, so adding a few basic map markers, or simplifying cyberspace combat for those who hate that style of gameplay, is a worthwhile addition if it encourages a modern audience to stick it with it long enough to understand and appreciate the genre’s distinctive player-driven flow.

All of which brings me to what I love most about System Shock (2023) and the genre as a whole. A good immersive sim punishes a player for a thoughtless approach and sloppy execution, but rewards preparation, planning, and the smart or unconventional use of the tools provided. It’s a genre that facilitates save-scumming, but not to encourage a trial-and-error approach; rather, it allows the player to iterate on a plan and master its execution. An ambush or boss fight shouldn’t require constant quick saving behind every piece of cover to manipulate the odds of being hit; you should want to reload a boss fight because you’ve thought of a way to optimise your approach and finish them off more efficiently.

System Shock (2023) features a handful of mandatory boss fights and ambushes, but most can be subverted by finding alternate paths; engaging in some minor sequence-breaking using the upgraded jump boots; or simply burning through stockpiled ammunition and consumables to trivialise battles. An early boss encounter against a cyborg Diego can play out as a panicked firefight that has you scrambling to dodge plasma rounds and flee as he teleports in close with a laser rapier. Alternatively, you could apply a Reflex Reaction Aid to slow time, a Berserk Combat Booster to buff melee damage, charge in and finish him off with a flurry of your own laser rapier before he can even trigger his teleport.

The same flexibility applies to conspicuously empty rooms that scream: “ambush”. You could also bolster yourself with dermal patches in preparation for a slow-mo scrap, or you could fling disc-like proximity mines at every wall panel, engage your shield mod, and rush to the middle of the room to watch your foes disintegrate in a flurry of explosions around you.

Of course, with a limited inventory and storage options, the tools at your disposal are dependent on your willingness to explore, backtrack, and prepare. There’s almost always enough to get by – even within boss arenas if you survive long enough to find them – but cautious and systematic explorers are rewarded with early access to powerful weapons, mod and weapon upgrades, and no shortage of character-enhancing dermal patches and meds.

Wrapping up, I’d reiterate my argument that a good immersive sim should ensure players can always progress using the tools or mechanics provided, conventionally or otherwise; it should reward them for exploration, preparation, and planning; and punish them for thoughtlessness or scrappy execution. I’ve played far too many modern games that, while often technically impressive and mechanically polished, are so reliant on familiar and effortless gameplay – the idea that player friction should be minimised – that my brain switches off and I run on autopilot until the next set-piece or elaborate cutscenes regains my attention.

A good immersive sim may lack that scripted spectacle and controlled pacing, but I prefer games where the minute-to-minute gameplay – that essential “game” part of videogame – is consistently engaging and rewarding. If you feel the same, the immersive sim genre is well worth your attention and the System Shock (2023) remake is one of many excellent options available on console and PC.

System Shock (2023) was played on Xbox Series S|X. It is also available on PC, Xbox One, and PS4/5.