The Alters is a streamlined and mechanically satisfying survival-game that also asks the question: what would you do if literally faced with the branching possibilities of the choices you never made?

The overarching plot slowly drifted into the back of my mind the longer I played, but The Alters has an intriguing premise that draws on several classic sci-fi tropes to turn a traditional survival game, with a strong focus on time management, into a thought-provoking journey filled with moments of frustration, elation, and unexpected warmth.

Jan Dowski, a 35-year-old builder who has already accumulated a lifetime’s worth of regrets, emerges from a landing capsule on an alien world. He soon discovers his captain and crew are dead, and although their massive, wheel-like is base is intact, the engines are offline – a severe problem when the approaching sunrise in this triple star system will bathe the area in lethal radiation.

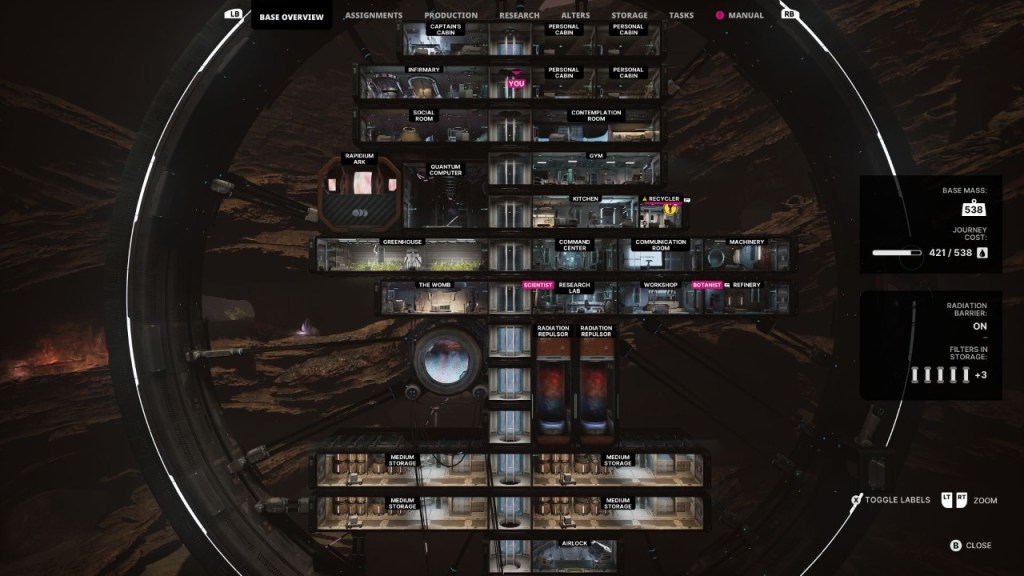

After exploring for some basic resources and establishing a distorted communication link to the Ally Corporation funding the mission, Jan discovers the base’s quantum computer, the “Womb” cloning facility, and the rare element “Rapidium” found on the planet, offer him an unconventional means of survival: cloning himself to create a new crew – the titular “Alters” – by imprinting their minds with specialised knowledge and simulated life-paths based on different decisions made at key moments in his digitised memory timeline.

The more you think about it, the more dubious science and plot-holes you can spot in The Alters, but 11 Bit Studios gets around this by keeping the entire experience surreal. Is the Jan Dowski you are playing as really the original? What should you make of the fact every Alter’s life path converges on joining the Dolly Missions at 35? What is the fate of the Alters if they return to this timeline’s Earth? If interstellar travel and quantum computing are commonplace in this universe, why is the search for the time-manipulating Rapidium so important to humanity’s survival?

I think what I like most about The Alters is how little those details mattered when I was engaged with the minute-to-minute gameplay and watching my growing Alter crew interact with one another.

I’d describe The Alters as a hybrid of traditional third-person exploration game and a time-management-heavy survival game, just with a weird and wild crew management twist.

Upon arriving in a new region, you explore on foot during so-called “daytime” hours – periods of low light and radiation levels – to discover and clear paths to resource deposits, build mining outposts and connect them with pylons, scan and destroy anomalies, find scattered mission gear for base upgrades, personal belongings to boost Alter morale, and later track down even weirder alien samples used for higher-tier research. It looks and feels suitably hands-on and immersive, though after establishing a resource chain, the bulk of your playtime is going to be spent interacting with base functions, engaging with Alters, or navigating assignment, production, and research menus.

The escalating resource and crafting requirements needed to survive and progress are streamlined compared to many of its peers, but time is always your enemy in The Alters. Efficient working hours are limited without enforcing mood-sapping crunch; the approaching sunrise shortens the time you can spend outside without racking up radiation burns; and a crew of alternate personalities are far more challenging to sustain than the generic staff you’d see in a game like XCOM. You’re not just building dormitories, labs, workshops, and radiation shields; you’ll also need to consider personal cabins, social facilities, contemplation rooms, and gyms.

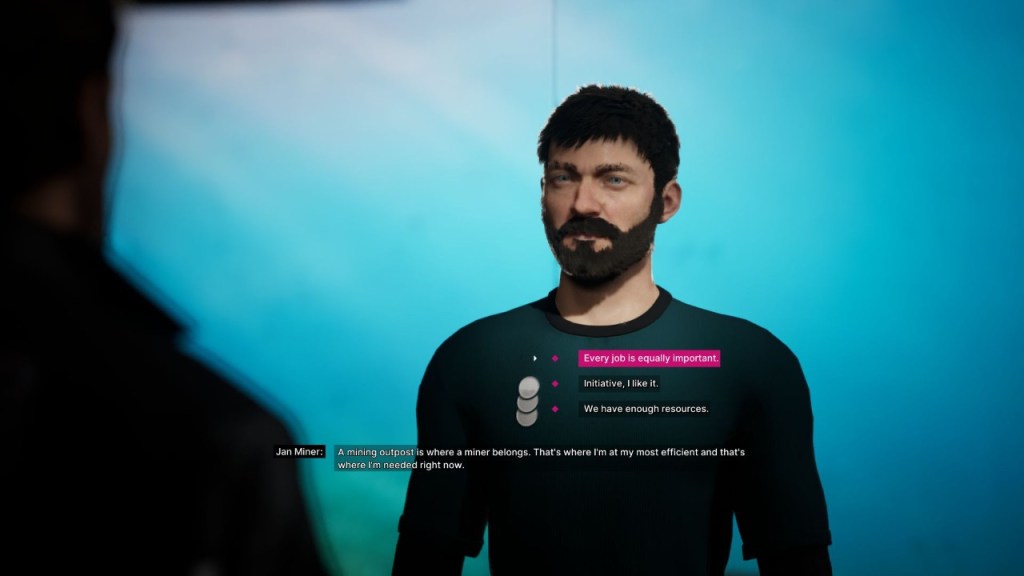

Each branch from Jan’s original timeline can result in wildly different personalities, with different anxieties, motivations, and triggers; all of which you’ll want to read up on in the simulated timeline before considering your responses in dialogue or when faced with suggestions. You will have to balance competing requests, deal with the fallout, and keep them all fed, physically healthy, mentally healthy, and entertained. Not treating your Alters as individuals is the quickest way to foster rebellion and jeopardise the mission when they ignore your orders or work inefficiently.

Regardless of the difficulties you pick for the game’s economy and action elements, you need empathise with your alternate Jans and occasionally boost their morale with gifts, social activities like beer pong and movies, and considering personal requests. It is impossible to clone every Alter variant and experience every potential outcome in a single playthrough, but good relationships teach Jan new life lessons that provide unique dialogue options, open new research paths, and alter the end-of-act outcomes.

There is a lot to juggle as the clock marches on, but all the assists you could want are present. With enough Alters, the early exploration step gives way to a lot of menu-based gameplay as you quickly build and rearrange base modules, assign Alters to resource or production tasks, select research priorities, and set minimum stock levels or continuous production queues to maintain essentials like food, radiation filters, and repair kits for the sporadic magnetic storms that devastate base modules and hamper most outdoor activities.

The chosen difficulty coupled with your skill at managing both time and Alters will determine if the mission plays out as scrappy and desperate attempt to survive on the edge, or as a well-oil machine that keeps on top of objectives and ahead of the sunrise with minimal trauma and injuries to the crew. That said, there are a few narrative beats that happen regardless of your actions.

With the focus on crew interactions as much as it is on the survival mechanics, it helps that The Alters mid-tier price-point does not mean low production values. Like most survival games with base-building and menu-driven systems, The Alters gets a lot of playtime out of limited assets, but it feels polished and the compact environments – both the expanding base and increasingly vertical outdoor regions – look incredibly detailed and atmospheric. Character models also look good, with only a few stiff animations during emotive gestures or while climbing.

More important is the writing, voice work, and delivery – both during moments where the Alter’s divergent personalities clash, and those in which they share cherished memories or establish new bonds. There are generic lines for common events and gameplay triggers, but I found it easy to empathise with Jan in all his forms. His Alters are exaggerated archetypes but they do an impressive job of leaving you frustrated with their vices, like pride, stubbornness, or self-pity, yet it also often left me elated during moments of unexpected compassion and warmth.

All that said, I’m no psychologist or support worker with professional experience, so you might find the lack of subtlety in how some mental health issues are presented problematic.

Even as someone who prefers methodical games that move at my pace over those with time pressures, I enjoyed The Alters far more than I expected. Not so much for the survival gameplay – which is competent, streamlined, and challenging enough in its own right – but more for the thrill of discovering what new Alter I could create, discovering how their lives played out compared to the original Jan Dowski, and watching them bond or clash with one another under increasing pressure.

I’m not sure if the writing and performances are quite good enough to compete with overproduced, “AAA”-style cinematic adventures with their ridiculous budgets, but The Alters actually got me thinking about whether you could ever stay sane if given the knowledge of the near infinite possibilities of all the decisions you’ve never made.

Pros:

- An intriguing setting with a weird and wild crew management twist

- Streamlined but satisfying survival and time management mechanics

- A gorgeous alien world to explore and solid voice acting

- Recreating the high school band with your Alters

Cons:

- Possibly too much menu-driven gameplay for some

- Early challenges can feel unforgiving if you pick the wrong Alter type or research path first

Score: 9/10

The Alters was reviewed on Xbox Series S|X using a code provided to gameblur by the publisher. It is also available on PC and PS5.