The first thing that comes to mind when thinking about Sovereign Syndicate is how excellent writing can carry mechanically and visually underwhelming games – so long as you have an audience willing to read. At first glance, Sovereign Syndicate looks to chase the Disco Elysium formula, turning your protagonists’ internal dialogue and resultant personalities into the equivalent of traditional RPG classes. However, the longer you play, the more you’ll realise their starting attributes and evolving personality add flavour to the journey rather than function as hard skills-checks.

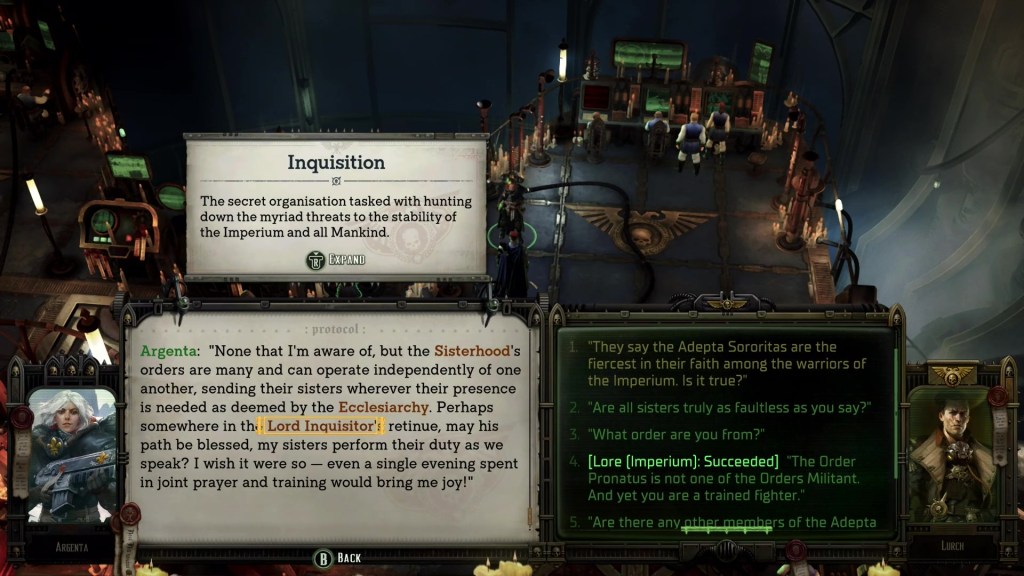

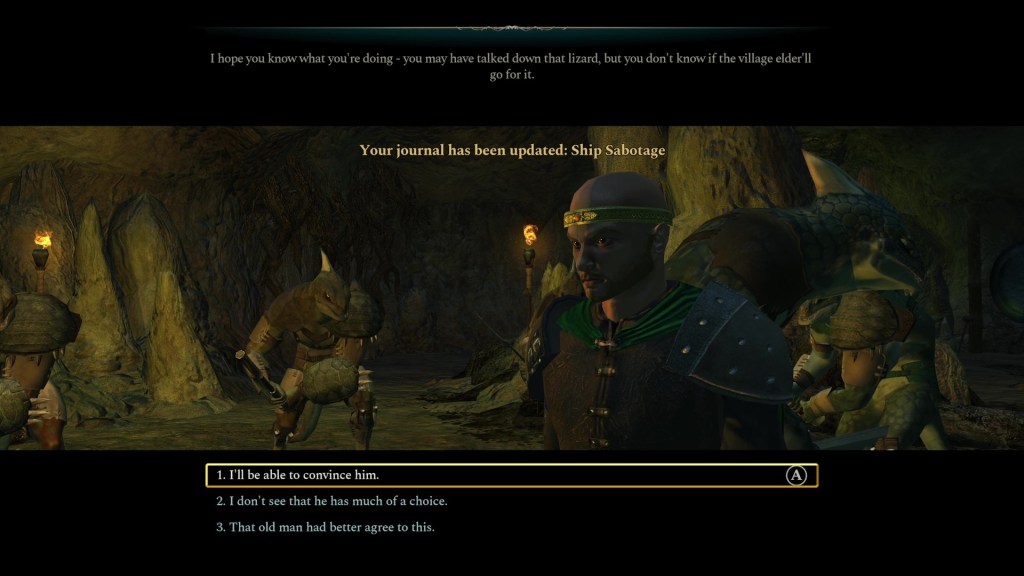

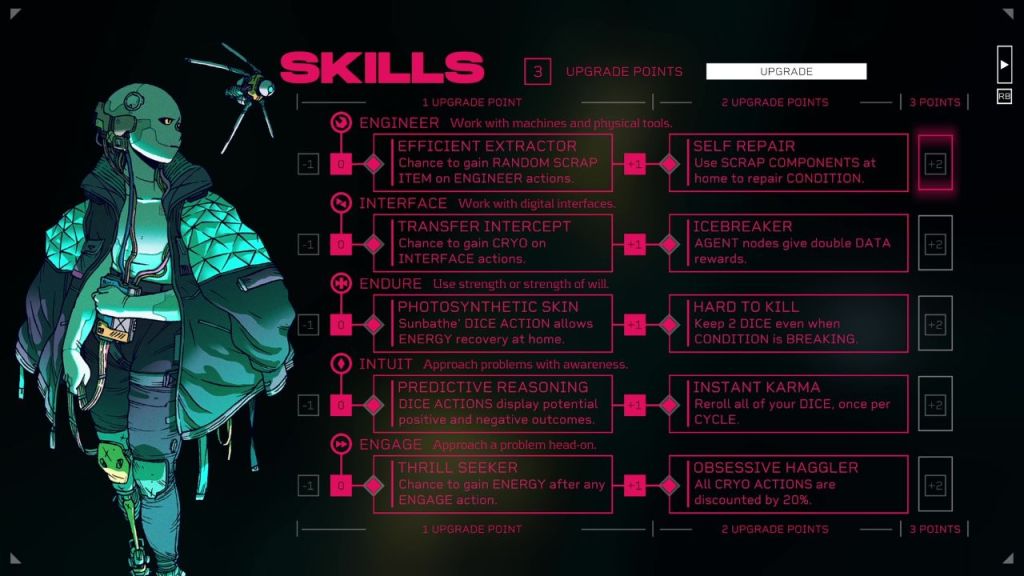

Sovereign Syndicate is still a role-playing game in the sense that you shape the decisions the protagonists make, unlock new response types as a result of their experiences, and influence their outlook on the world. The more effort you put into tackling the secondary content, the more dialogue options you give yourself down the line. However, the initial character class and stylish Tarot card system are just another form of dice roll modifiers, and you can always save-scum your way through any skill-check if you really wanted to.

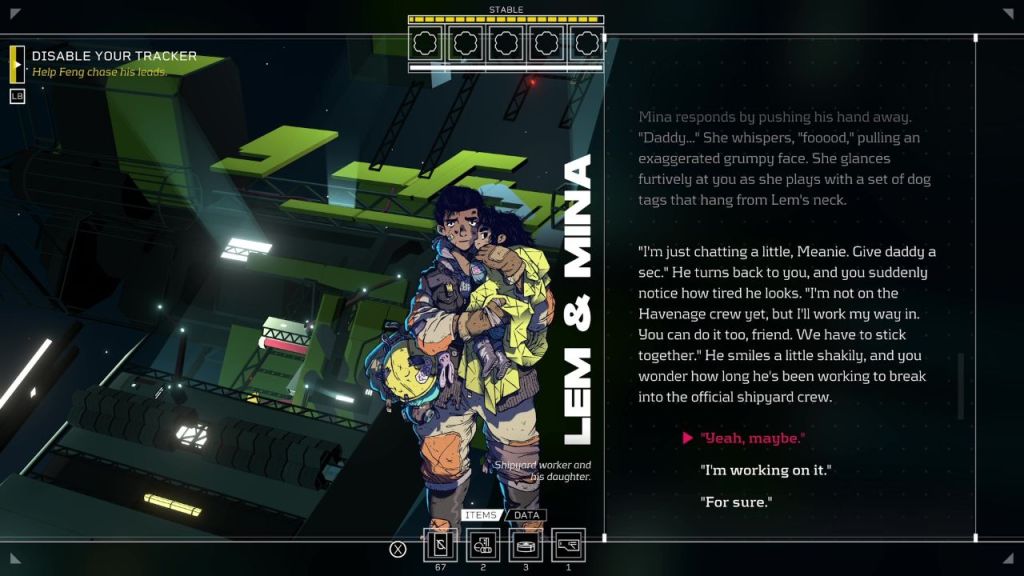

That flexible structure and a focus on lengthy dialogue sequences can make Sovereign Syndicate feel closer to a visual novel with light RPG elements, but that’s no bad thing for those that enjoy reading and using their imagination fill out details that the inconsistent visuals and artwork cannot provide. Set in a Victorian-era London, where steampunk technology and low-fantasy magic coexist, Sovereign Syndicate takes you on a lengthy journey that switches back and forth between three characters, and there’s plenty of minor details and interactions to embellish.

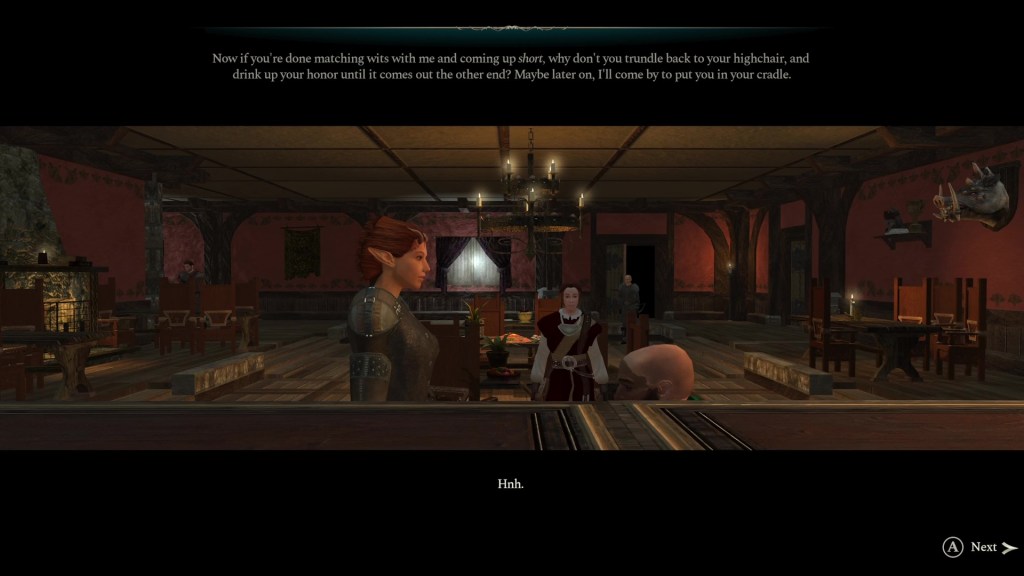

Atticus Daley is a minotaur trying to drink away his troubled orphan past, before a mysterious stranger with gun and a new nagging voice in his head set him on a quest to discover the fate of his mother. Clara Reed is a human courtesan tired of entertaining London’s elite and looking for a way to raise enough money to smuggle herself across the Atlantic. Teddy Redgrave is a dwarf and war veteran, who now spends time tweaking his automaton “Otto” and taking contracts to hunt down mythical beasts and common vermin plaguing London. It is an eclectic cast with different views on the world and characters around them, and each takes the lead on investigating secondary plot lines that run throughout the adventure.

That structure ties into the verbose writing that, while not always consistent in delivery, is wonderfully intricate and expressive. Dialogue with key NPCs, internal monologues, and observations of the world around them are unique for each character. This allows the developers to flesh out every character and dole out heaps of worldbuilding; it provides the player much better insight into the motivations of each protagonist; and simply makes exploring the world incredibly satisfying – albeit only if you’re willing to read.

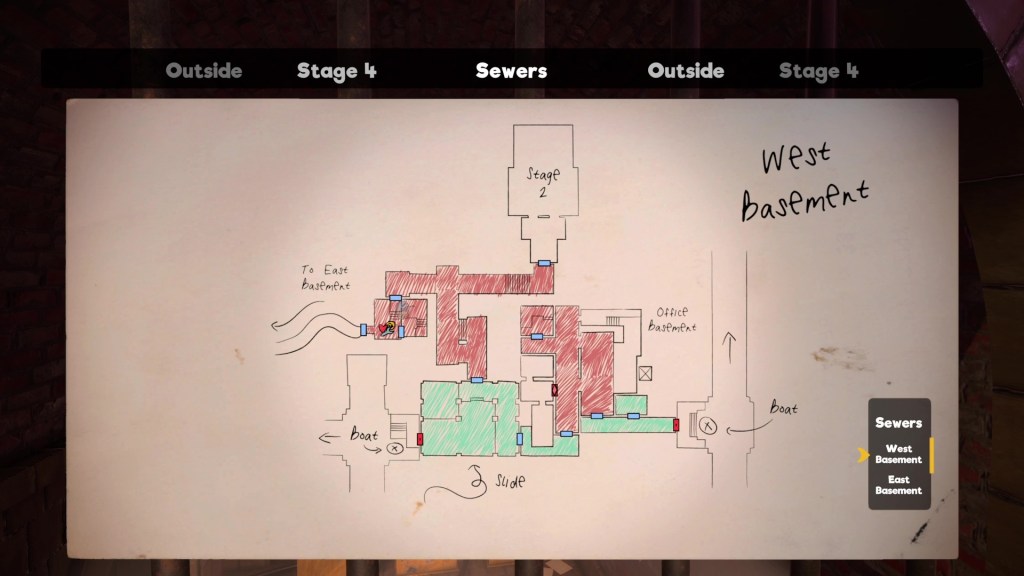

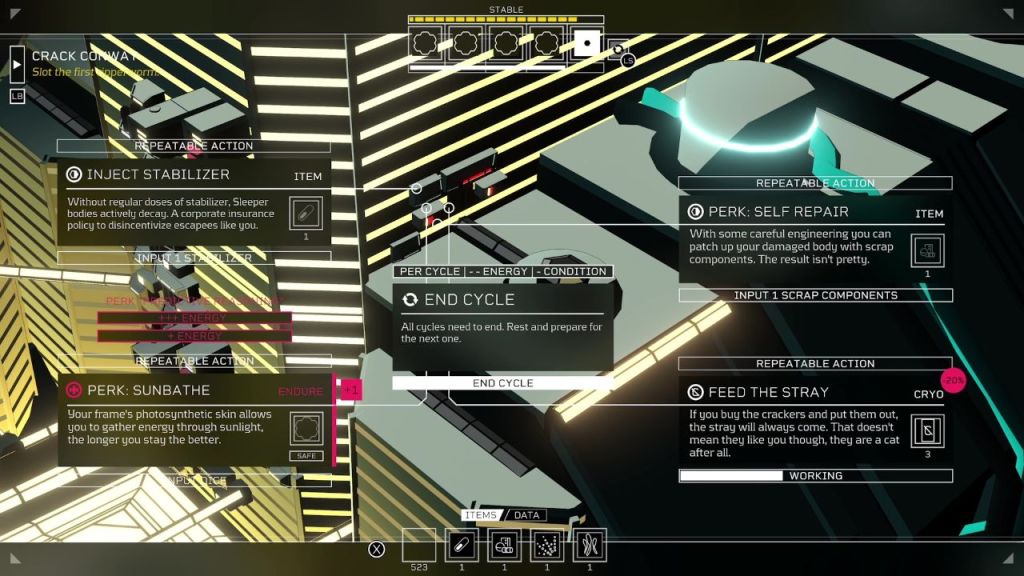

In contrast, the gameplay mechanics feel perfunctory and drawn out you traverse several areas of London repeatedly, talking to everyone you can in each chapter to ensure you don’t miss important interactions or clues that update quest entries. Tarot card draws for dialogue challenges and environmental interactions are just dice rolls. You have an inventory but there’s little reason to ever open it as key items are flagged in conversations or during interactions when needed. It can grow increasingly tiresome and left me wondering if Sovereign Syndicate would have had better pacing if it gone for map- and menu-driven exploration similar to visual novels or point-and-click adventure games.

That said, Sovereign Syndicate still feels unique and there is little like it on consoles aside from the aforementioned Disco Elysium. It feels like a fantasy-steampunk adventure novel recreated in video game form, and it’ll be a treat for those who enjoy visual novels or those who pore over lore documents in games. You could accuse the writers of overcomplicating or embellishing elements, but I loved the detailed internal monologues, frequent exposition, rich flavour text, and the minor changes to my options as each character evolved. If a visual novel/RPG hybrid with great writing is your idea of a good time, don’t pass up on Sovereign Syndicate (and I hope there’s a Nintendo Switch port at some point).

Sovereign Syndicate was played on Xbox Series S|X using a code provided to gameblur by the publisher. It is also available on PC and PS5.